Read for Free

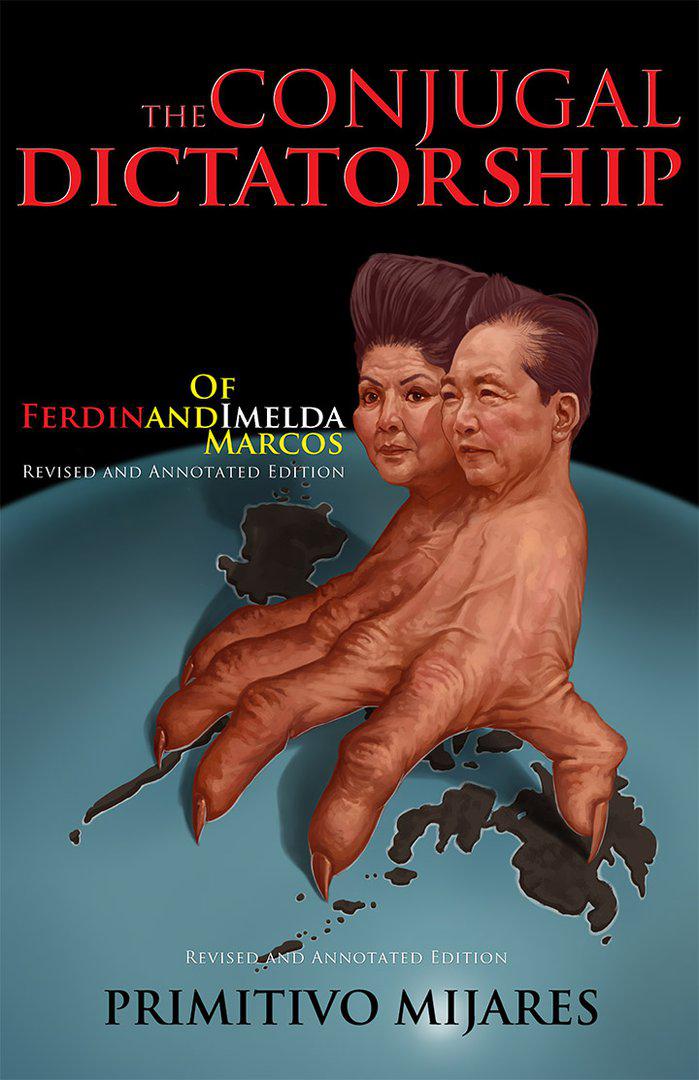

Read The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos free online.

Introduction

Dedication

To the Filipino people, who dramatized in the Battle of Mactan of April 27, 1521, their rejection of a foreign tyranny sought to be imposed by Ferdinand Magellan, that they may soon recover lost courage and, with greater vigor and determination, rid the Philippines of the evil rule of a homegrown tyrant with the same initials and first name.

Foreword to the 2016 Edition (Rene Saguisag)

I first read The Conjugal Dictatorship by courageous Primitivo “Tibo” Mijares in 1976, surreptitiously, not openly. In those days, everybody was afraid of martial law—it was the reign of terror—but I have learned the art of pretending not to be afraid. I became a human rights lawyer, an unknown animal when I was in San Beda Law, LL.B.’63, and in Harvard Law, LL.M.’68.

I had two copies of the book that I acquired in 1976 from friends in the U.S. defying the conjugal dictators, which I passed on and never got back from borrowers who kept passing the book around. The book gave its readers a ringside seat on the inner workings of the Marcoses in Malacañang. Its contents certainly helped trigger the revolution of February 1986 that toppled the conjugal dictators from power.

Very recently, I got another copy of the book and it brought back memories, from the sublime (the Resistance Movement) to the ridiculous (e.g., Chapter X, on the “Loves of Marcos”).

Raissa Robles’s new book, Marcos Martial Law: Never Again, begins with the story of Boyet, a teenaged son of Tibo Mijares. In May 1977 a military chopper dropped Boyet’s tortured, lacerated, and mutilated dead body in Antipolo—again, a testament to Marcosian fury. The teenage Mijares was guilty of nothing save that his father had written a book. The Marcoses in effect royally said: “We are not amused.” They got their pound of flesh in egregious inhumane fashion.

Tibo was one of five people Marcos saw regularly. He defected in 1975. He knew too much and so informed a Congressional Committee in the U.S. in June 1975, in the United States House of Representatives Sub-Committee on International Organizations of the House Committee on International Relations headed by Representative Donald Fraser of Missouri. As a result of his defection and subsequent testimony against his former boss, Tibo was lined up for liquidation. As a popular Filipino saying goes, lintik lang ang walang ganti.

After delivering his testimony, Tibo mysteriously disappeared. No one who knows for certain how he died, but the urban legend says that like his son, Tibo’s body was dropped off an aircraft (between Manila and Guam). His body was never found.

Kindly read the book and tell me why Tibo does not deserve to be memorialized in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, where Marcos, to be sure, does not belong. No narrative of the martial law era would be complete without Tibo’s priceless contribution. He also clearly belongs in the Bantayog ng mga Bayani.

Indeed, martyred Tibo and Boyet—mga nagbuhos ng dugo para sa bayan, kagitingang hindi malilimutan. Any fair-minded reader of the book will understand why the remains of Marcos must remain in the North and why Tibo and Boyet will always have a place, somewhere in our heart of hearts.

Author's Foreword (Primitivo Mijares)

This book is unfinished. The Filipino people shall finish it for me.

I wrote this volume very, very slowly. I could have done with it in three months after my defection from the conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos on February 20, 1975. Instead, I found myself availing of every excuse to slow it down. A close associate, Marcelino P. Sarmiento, even warned me, “Baka mapanis ’yan.” (Your book could become stale.)

While I availed of almost any excuse not to finish the manuscript of this volume, I felt the tangible voices of a muted people back home in the Philippines beckoning to me from across the vast Pacific Ocean. In whichever way I turned, I was confronted by the distraught images of the Filipino multitudes crying out to me to finish this work, lest the frailty of human memory–or any incident a la Nalundasan—consign to oblivion the matters I had in mind to form the vital parts of this book. It was as if the Filipino multitudes and history itself were surging in an endless wave presenting a compelling demand on me to San Francisco, California perpetuate the personal knowledge I have gained on the infamous machinations of Ferdinand E. Marcos and his overly ambitious wife, Imelda, that led to a day of infamy in my country, that Black Friday on September 22, 1972, when martial law was declared as a means to establish history’s first conjugal dictatorship. The sense of urgency in finishing this work was also goaded by the thought that Marcos does not have eternal life and that the Filipino people are of unimaginable forgiving posture. I thought that, if I did not perpetuate this work for posterity, Marcos might unduly benefit from a Laurelian statement that, when a man dies, the virtues of his past are magnified and his faults are reduced to molehills.

This is a book for which so much has been offered and done by Marcos and his minions so that it would never see the light of print. Now that it is off the press, I entertain greater fear that so much more will be done to prevent its circulation, not only in the Philippines but also in the United States. But this work now belongs to history. Let it speak for itself in the context of developments within the coming months or years. Although it finds great relevance in the present life of the present life of the Filipinos and of Americans interested in the study of subversion of democratic governments by apparently legal means, this work seeks to find its proper niche in history which must inevitably render its judgment on the seizure of government power from the people by a lame duck Philippine President.

If I had finished this work immediately after my defection from the totalitarian regime of Ferdinand and Imelda, or after the vicious campaign of the dictatorship to vilify me from July to August, 1975, then I could have done so only in anger. Anger did influence my production of certain portions of the manuscript. However, as I put the finishing touches to my work, I found myself expurgating it of the personal venom, the virulence and intemperate language of my original draft.

Some of the materials that went into this work had been of public knowledge in the Philippines. If I had used them, it was with the intention of utilizing them as links to heretofore unrevealed facets of the various ruses that Marcos employed to establish his dictatorship.

Now, I have kept faith with the Filipino people. I have kept my rendezvous with history. I have, with this work, discharged my obligation to myself, my profession of journalism, my family and my country.

I had one other compelling reason for coming out with this work at the great risks of being uprooted from my beloved country, of forced separation from my wife and children and losing their affection, and of losing everything I have in my name in the Philippines — or losing life itself. It is that I wanted to make a public expiation for the little influence that I had exercised on the late Don Eugenio Lopez into handpicking a certain Ferdinand E. Marcos as his candidate for the presidency of the Philippines in the elections of 1965. Would the Filipinos be suffering from a conjugal dictatorship now, if I had not originally planted in Lopez’s consciousness in 1962 that Marcos was the “unbeatable candidate” for 1965?

To the remaining democracies all over the world, this book is offered us a case study on how a democratically-elected President could operate within the legal system and yet succeed in subverting that democracy in order to perpetuate himself and his wife as conjugal dictators.

I entertain no illusions that my puny work would dislodge Ferdinand and Imelda from their concededly entrenched position. However, history teaches us that dictators always fall, either on account of their own corrupt weight or sheer physical exhaustion. I am hopeful that this work would somehow set off, or contribute to the ignition, of a chain reaction that would compel Marcos to relinquish his vise-like dictatorial grip on his own countrymen.

When the Filipino is then set free, and could participate in cheerful cry over the restoration of freedom and democracy in the Philippines, that cry shall be the fitting finish to this, my humble work.

April 27, 1976 San Francisco, California United States

Acknowledgement

I would need an additional chapter in a futile attempt to acknowledge all the help I received in producing this volume. However, I would be extremely remiss, if I did not acknowledge my debt of gratitude to the librarians at the Southeast Asia Center, University of California at Berkeley, and the thousands of Filipinos in the United States and back home in the Philippines whose enthusiasm for, and dedication to, freedom and democracy guided my unsteady hands in an unerring course to finish this work.

No comments yet. Login to start a new discussion Start a new discussion